SIGNS OF LIFE

New Orleans and Other Projects

These works are presented here to provide an introductory overview and to demonstrate a long-term commitment to the medium of photography. They should not be construed as defining the current or future directions of the work.

All site content © Charles Silver all rights reserved.

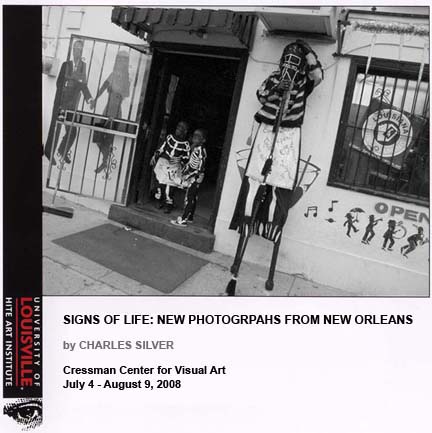

SIGNS OF LIFE: NEW PHOTOGRAPHS FROM NEW ORLEANS

NOW AVAILABLE FOR BOOKINGS

This first installment in the ongoing photodocumentary project by Charles Silver had its premier exhibit at the Cressman Center Gallery for Visual Art from July 4 to August 9, 2008. Interested parties may inquire through the Gallery or use this link to Contact Charles Silver directly regarding arrangements.

These photographs represent the starting point for long term ongoing projects documenting New Orleans in the post-Katrina environment. Three years after Katrina large parts of the city and its communities remain physically and psychologically devastated. Now even more devastation is threatening the city.

The project has concentrated on some of the endangered African American cultural traditions that are unique to New Orleans.

The majority of the photographs in this exhibit grew directly out of the concerns and wishes of friends within the cultural community of New Orleans. This community not only gave birth to Jazz but has also given birth to a range of cultural traditions unique to New Orleans. These traditions include Second Lines with brass bands, Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs and the Black Mardi Gras Indian tribes. Since the vast physical devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 many socio-economic and political forces have further endangered these valuable cultural traditions.

Several sets of subjects are represented:

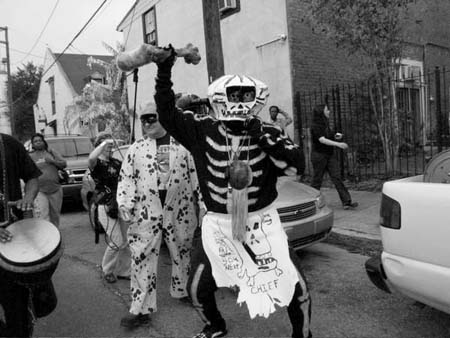

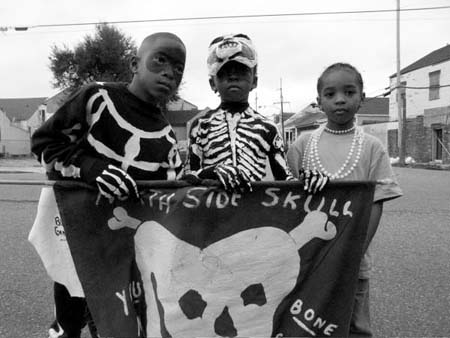

The grouping entitled Shadows and Spirits documents a relatively unknown aspect of Mardi Gras celebrations from the parallel folk traditions practiced in the Carnaval Noir/Black Carnival of the New Orleans African American community. This set features images of one of the oldest masked parading groups of Mardi Gras. The North Side Skull and Bones Gang, which dates from 1819 in New Orleans. The roots of these parading skeletons can be traced back to Carnival traditions of the Carribean, Mexico, Central and South America and Europe. Included in this set are images of a "call out", a call and response exchange between members of the Bone Gang and the community.

Related subjects include some images representative of the brass band and jazz band traditions as embodied by the Treme Brass Band, some images representative of the Black Indian 'tribes' of New Orleans more popularly known as Mardi Gras Indians.

For context I have included a few other images related to New Orleans as a place rather than to any particular subculture.

Also included is a group of images from the Mardi Gras celebrations of the Gay community in the North Bourbon Street area of the French Quarter.

With LOVE from New Orleans - 2008

Introduction: A brief note on the Treme, St. Augustine's church, slavery and racial exclusion:

To understand New Orleans in context it is necessary to understand the complex racial issues which began with the city's founding, with slavery and which continue in part to underly the socio-economic realties of the city to this day. I cannot do such a vast subject justice here. However, I will mention that slavery, its permutations and consequences that still generally effect the sociological landscape of the U.S. also weigh especially more heavily upon many of the invaluable cultural aspects of New Orleans.

The Treme neighborhood which begins just one block west of the French Quarter across Rampart Street is the oldest African American community in New Orleans. This area is still central to many of the folk and cultural traditions represented in the photographs. Louis Armstrong Park lies just south of Treme and the park contains many historic features including the site of the original Congo Square. Congo Square is noted as the only public space where slaves were permitted to gather and socialize. It was there that oral traditions and folk traditions from Africa such as drumming, dancing and music were practiced, maintained and passed on. It was here that these African traditions blended to some extent with similar local indigenous Native American traditions. In the heart of the Treme stands St. Augustine's Catholic Church which is currently under threat of closing. St. Augustine's has a very rich and interesting history that is worthy of further exposition.

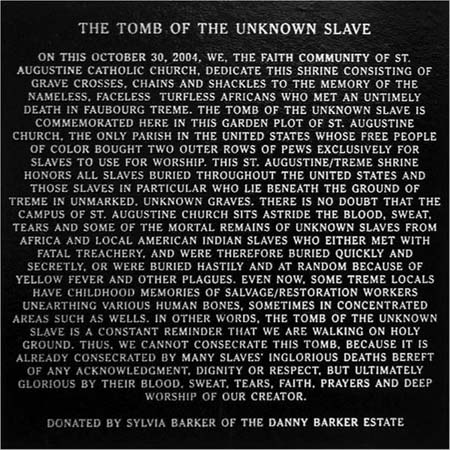

Outside of St. Augustine's is a memorial and a plaque which I believe is an important clue in understanding the tensions between the cultures of the elites and the excluded. It may serve as a useful model for beginning to understand and heal some of the old wounds of race relations and move forward, together in the larger context of these issues remaining throughout the U.S. today. It may also help clarify some of the forces and counterforces that have been born from the past and present collisions of these two cultures that has resulted in the unique cultural treasures and heritage of New Orleans.

To highlight this history I have included a reproduction of the plaque and a photograph of the memorial at St. Augustine's church in the Fauborg Treme:

Memorial Plaque - Tomb of the Unknown Slave - New Orleans - 2008

Tomb of the Unknown Slave - New Orleans - 2008

Part 1 - NEW ORLEANS IS DREAMING - New Orleans as Place:

Fortune - New Orleans - 2008

Masks at Jackson Square - New Orleans - 2008

Open Daily - New Orleans - 2008

Loss - New Orleans - 2008

Trust - New Orleans - 2008

Together - New Orleans - 2008

SKULL AND BONE GANGS: an ammended exhibition text from the Carnaval Noir exhibit curated by Judy Boudreaux at McKenna Musuem of African American Art, 2003 Carondolet Street, New Orleans:

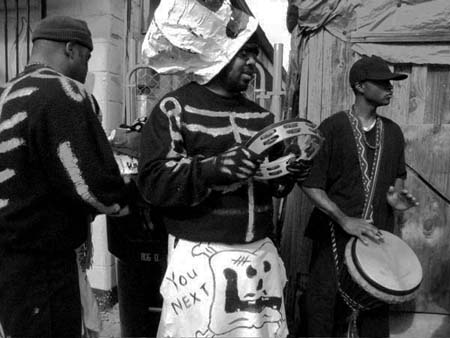

"Too late ... its too late," the Bone Gang warns us that death is unpredictable yet inevitable, so live right today, and they remind us to enjoy today. "Scared straight" describes the frightening role of the Bone Men since 1819, welcoming in Carnival's dawn. From cemeteries they rise to preserve the "oldest" Indian tradition in New Orleans.

Every year in New Orleans the "Skeletons" are the first to kick-off Mardi Gras Day customs and traditions. They are known for taking to the streets before sunrise beating drums and shouting chants to wake up Carnival.

Best known of all, The North Side Skull and Bones Gang is a kind of secret society. Its living oral traditions were most recently passed down to "Big Arthur" then to Big Chief Bone Man Al Morris and to Chief Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes. Donning handcrafted over-sized skulls and skeleton suits, wearing butcher's aprons and carrying freshly butchered gigantic animal bones, they can be seen waking the community in the old Treme neighborhood.

Very early on the morning of Mardi Gras Day with tambourines, drums and shouts of "Skull and Bones ! ", "Bone Gang's here ! " and other chants and alarms that echo down the empty streets, the Bone Men make their way through the old neighborhoods. They run onto porches and using gigantic ham bones they knock on doors and go into homes where they yell "Wake Up ! You Next !" and can be seen challenging sleepy children: "Did you do your homework ? Don't Lie to me, I'll know. If you don't do your homework you're going to see me again, tonight."

Similarly dressed Skull and Bone gangs can be found parading through the streets during Carnival celebrations throughout the Caribbean, Central America, the West Indies and Africa.

Some theorize that like Carnival, the Skull and Bone gangs originated in Europe in the fifteenth century. Skeletons appeared as apparitions and as embodiments of the concept of 'memento mori' ("remember that you are mortal," "remember you will die") during Carnival and Lent. Others say that the spiritual presence of the Skeletons echoes the calacas of Indigenous Mexico's Dia de los Muertes (Day of the Dead) and Haitian Voudun's Barron Samedi (loa of death-like Orisha of Santeria or The God of Christianity).

Not only are they often spotted parading with the Mardi Gras Indians, they also maintain a similar hierarchy within their organizations. Skull and Bone gangs just like the Mardi Gras Indians have a chief, a second chief, a spy boy, a flag boy and a wild man. There are other similarities as well. Such ancient rituals preserve customs and traditions from generation to generation. They also illustrate the complexity of African and Indigenous cultural survival amidst New World Colonial Creolization.

Wake Up ! - New Orleans - 2008

Skull and Bones - New Orleans - 2008

Bone Man - New Orleans - 2008

You Next ! - New Orleans - 2008

Listen - New Orleans - 2008

Next Generation - New Orleans - 2008

Blessing - New Orleans - 2008

Guardian - New Orleans - 2008

Signs of Life - New Orleans - 2008

Come Home - New Orleans - 2008

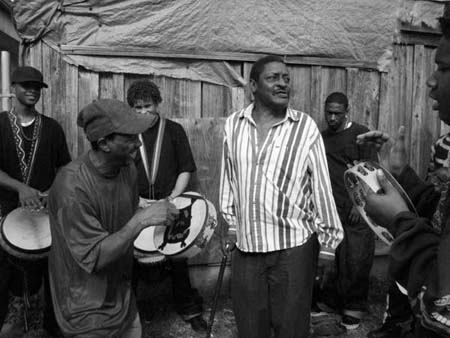

Call Out 1 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 2 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 3 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 4 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 5 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 6 - New Orleans - 2008

Call Out 7 - New Orleans - 2008

Rhythms - New Orleans - 2008

Backstreet - New Orleans - 2008

Gate Keeper - New Orleans - 2008

SACRED GROUND:

The acting Big Chief of The North Side Skull and Bones Gang, Big Chief Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes, described his Mardi Gras preparations in this excerpt from an article SACRED GROUND - By David Winkler-Schmit, from The Gambit Weekly that appeared during Carnival, 2008.

For many New Orleanians, Mardi Gras is a neighborhood cultural celebration. In the wake of Katrina, one of the city's oldest neighborhoods -- Treme -- clings to its traditions against a tide of change.

Early in the morning, Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes begins his Fat Tuesday preparations to march with the Northside Skull and Bones Gang.

On Fat Tuesday, Mardi Gras Indians converge on Claiborne Avenue under the I-10 overpass. For Bruce 'Sunpie" Barnes, Mardi Gras day begins quietly in the darkened pre-dawn hours as he takes a solitary journey to a local cemetery to commune with the dead. Kneeling before graves, he asks the spirits of the past to enter his body so that he can become their living vessel, joining his soul with theirs as he takes to the streets. Later, at sunrise, he emerges in full costume, calling out and waking up the Treme neighborhood with his group, the Northside Skull and Bones Gang, which has followed the Carnival tradition for decades.

"We'll bring all the past dead spirits to the streets," Barnes says. 'Mardi Gras is the one day we do that."

Gate Keeper Ronald W. Lewis and Big Chief Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes - New Orleans - 2008

Skull and Bones - New Orleans - 2008

"We just call that the "800 block" and everyone knows what it means." - Quote from a former New Orleanean

One of the special qualities of New Orleans is how so many people of diverse backgrounds and tastes co-exist in relative harmony. Of course there are many underlying tensions. Rarely it seems, does trouble occur and usually it is a clash of economics not culture or subculture. People seem to respect each other and practice a live and let live philosophy.

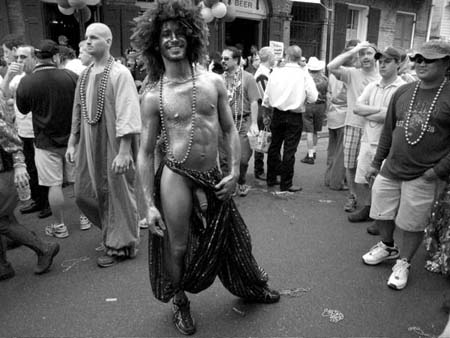

New Orleans is known as America's First Bohemia. Besides all of the well known cultural manifestations, the city has always attracted large numbers of artists, writers, rebels and outcasts of all sorts. The Gay community is just one of many of the important subcultural groups that add spice to the gumbo in this bohemia.

The history of the gay community like the history of the other subcultures of New Orleans is made up of names only known locally or, in some cases, known nationally or internationally.

It was very much a hidden but important subcultural community until the nineteen twenties when the first openly gay social club appeared. Since then, the visibility of the gay community has grown and progressively become more tolerated even if not totally accepted by everyone.

The two main examples of visibility now are the Southern Decadence Festival held around Labor Day each year and on Mardi Gras Day, the The Bourbon Street Awards which began at the intersection of Dumaine and Bourbon in 1964. Currently, the Awards usually begin around noon with a drag show on a raised platform at the intersection of St. Ann and Bourbon and culminate in the selection of The Queen. While the larger raucous Bourbon Street crowds revel from Canal down to Orleans the Awards celebration draws thousands of revelers both gay and straight.

Pale Blue - New Orleans - 2008

Frenchmen - New Orleans - 2008

A Toast - New Orleans - 2008

Two Belles - New Orleans - 2008

Blue Man - New Orleans - 2008

Watching the Parade - New Orleans - 2008

Happy Couple - New Orleans - 2008

Shoe People - New Orleans - 2008

The Living Dead - New Orleans - 2008

Mr. Goodsport - 2008

Second Chief Mohawk Hunters - New Orleans - 2008

Second Line Beat - New Orleans - 2008

Creole Wild West - Wild Woman - New Orleans - 2008

Uncle Lionel Batiste - New Orleans - 2008

Skeleton Man - Mowhawk Hunters - Algiers - New Orleans - 2008

Treme Brass Band - New Orleans - 2008

Mother and Son - Treme - New Orleans - 2008

Trickster - New Orleans - 2008

Big Chief Donald Harrison, Jr. - New Orleans - 2008

Feathered - New Orleans - 2008

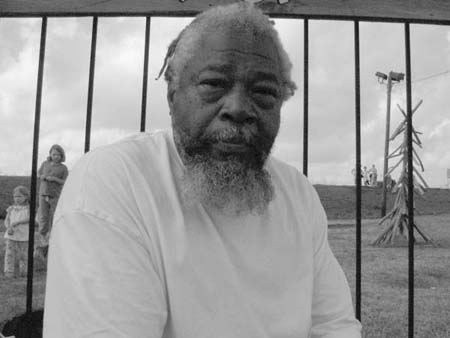

Malik Rahim - New Orleans - 2008

Malik Rahim and Sakura Kone - New Orleans - 2008

Ashton T. Ramsey - New Orleans - 2008

Additional Notes on Black Carnival and other traditions:

Carnival is a season of parades and celebrations of the flesh which can be traced to Europe. Carnival begins on the Twelfth Night of Christmas, January 6th, and ends at midnight on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent.

New Orleans was founded by the French and they call the last day of Carnival Mardi Gras which means "Fat Tuesday". Since the following day marks the beginning of six weeks of fasting and other privations, Mardi Gras Day is filled with a final frenzy of celebrations.

In New Orleans there are two parallel Carnival traditions. The first are the well known and highly publicized celebrations with both sanctioned mainstream Mardi Gras "Krewes" and the satirical Krewes that skewer the foibles of powers-that-be and social elites. This is the 'Mardi Gras' that draws large crowds and vast numbers of tourists.

This well known side of Mardi Gras began among the social elites of the city and for most of its history generally excluded participation by 'people of color' with the exception of the 'Flambeaux'', originally 'favored' slaves, who were permitted to carry torches to light the night time spectacles and those that follow behind the parades sweeping the piles of beads, trinkets and trash off the streets. One of the results of this type of exclusion are the folk traditions of the Carnaval Noir or Black Carnival which took root and finds expression in the African American community of the city.

There are several other traditions which originate in the African Amercan community which are unique to New Orleans and which have by extension become part of the Black Carnival. These include Brass Bands, Second Lines, Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs and the Black Indians of New Orleans.

Since the I-10 was built in 1969 all of these groups have been endangered to some extent. The interstate was built directly over Claiborne Avenue, the epicenter of the African American community. It destroyed the main area of social gatherings when the shade of the live oaks which filled the "neutral ground" (median) of the avenue were replaced by rows of concrete columns supporting a canopy of concrete interstate. Businesses were lost, as was part of the spirit of the community. Still, the community struggled on and held on to their traditions as best they could.

Since Katrina in August of 2005 these traditions have become even more endangered. Many community members were or still remain scattered across the U.S. and many will not be returning. Various socio-economic and political forces are at work which are at odds with the survival of these traditions.

The short version of the history of New Orleans Brass Bands claims they originated after Union Soldiers left New Orleans in 1877 when Reconstruction ended. The troops left many band instruments behind which were then put to use by musically inclined citizens. The combination of existing African American musical traditions with these band instruments resulted in the birth of the New Orleans style brass bands and ultimately the birth of Jazz music. The brass band tradition continues to this day. One of the more famous of them is The Treme Brass Band.

The term Second Line has multiple meanings. The meaning which is important in this context refers to the groups of people who parade, dance and celebrate while following a brass band. In general, anyone is welcome to join in a Second Line. Second Lines occur in a number of contexts which include such things as funerals, parades of Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs and during Carnival celebrations.

Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs arose across the city in various poor neighborhoods to create a social bond between community members. In these neighborhoods it was often impossible to purchase any kind of insurance. The clubs collect membership dues and donations to provide the members a type of insurance fund. Typically the club funds provide for the costs of funerals and burials of members and often contribute something to the surviving family.

Racial segregation has always played a role in New Orleans. The French Quarter is bounded on the west by North Rampart Street. Social Aid and Pleasure club parades, brass bands and second lines historically occur on the west side of Rampart as do gatherings of Black Indians and many larger social gatherings of the African American community.

Finally, and briefly a note about the Black Indians. They are often called Mardi Gras Indians because they are most visible during Mardi Gras. Much can and has been said of the Indians and there are many in depth written materials on the Black Indians of New Orleans.

Currently there are about thirty Indian tribes or gangs. It is commonly thought they first began their Mardi Gras traditions in the 1880's. There are at least two exceptions. The first tribe, The Creole Wild West claims to have documentation of the tradition in the 1750's. The North Side Skull and Bones Gang claim 1819 as the year of their origin. They are not strictly an Indian group but they do share a similar organizational structure: Big Chiefs, Spy Boys, Flag Boys, Wild Men, etc.

In any case, the Indians originated as neighborhood street gangs and until the late 1960's were often involved in actual turf wars. The late Big Chief 'Tootie' Montana worked successfully to turn the tribe's encounters into a contest of aesthetic 'warfare' rather than actual wars. Each year members must make a new costume by hand. The costumes are very colorful and include brilliant displays of feathers and intricate hand sewn panels of beadwork that usually illustrates a story.

Many members of the tribes are involved in maintaining the Indian traditions and more importantly are involved in various aspects of community building. Indians (and the Bone Men) come from many walks and stations of life. Among them are found educators, school principals, administrators, historians, skilled laborers, business leaders, musicians, film makers, artists and so on. They contribute a great deal of their spare time mentoring youth and promoting literacy, musicianship and other types of programs aimed at improving their neighborhoods and communities.

Over a long period of time I will remain involved with these individuals and cultural groups by offering my photography skills in service to them in my own effort to document, advocate for and help maintain their survival.

Acknowledgements for SIGNS OF LIFE:

This project and exhibit would not be possible without the help and encouragement of a large number of individuals and I would like to thank them all for their kind and generous contributions. First, thanks to my parents and grandparents for indulging my passion for photography. Many thanks to my partner, Marnie Olson. Her support through the years has made all of this possible. She is directly responsible for keeping me connected to my photography, making certain that I follow through on opportunities and the production of my work.

In New Orleans: Andy Levin photographer and organizer of Mardi Gras 360; my friends and mentors in New Orleans: Ronald W. Lewis, community historian, activist and, director of the House of Dance and Feathers cultural museum. In addition Ronald is the Gate Keeper of The North Side Skull and Bones Gang. Our friendship and his invitation to photograph the "Bones" Mardi Gras morning led directly to this exhibit and to many of my friendships and contacts in the African American cultural community of New Orleans. Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes, Park Ranger, museum and spiritual guide, historian, musician, scientist, renaissance man, acting Big Chief of The North Side Skull and Bones Gang. Royce Osborn, filmmaker (All on a Mardi Gras Day and Walking to New Orleans) another Skull and Bones man. Shantrelle Lewis director of the McKenna Museum of African American Art and curator Judy Boudreaux. Mark Sindler and Owen Murphy of the New Orleans Photo Alliance, Don Marshall of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival Foundation, Sylvester Francis of the Back Street Museum, Tyrone Casby, Sr., Big Chief of the Mohawk Hunters, Benny Jones, Sr., "Uncle" Lionel Batiste, the Treme Brass Band and Craig Morse. Many people and venues in New Orleans continue to contribute to my photographic goals, I'm sorry I can't list them all.

In Louisville: O.J. Connell for his encouragement. He has been a great friend, advisor and resource. Paul Paletti for his advice and continuing interest in my photographic work. Andrew Dailinger for his advice and guidance. At the University of Louisville: Special thanks to John Begley and Bruce Linn at the Cressman Center for Visual Arts Gallery, and, everyone at The Photographic Archives at the University of Louisville. Also, in Louisville, a long overdue and sincere thanks to Dorothy Cherry and the late Wendell Cherry for their generous support and belief in my potential. They made it possible for me to pursue many of my goals and develop as a human being and photographer. I will always be indebted to them.

Thanks also to my teachers, mentors and spiritual guides: Henry Holmes Smith, Helmut Hoffmann, Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, the Tibetan Rinpoches Taktser Lama (Thubten Jigme Norbu), Chogey Lama, Pema Norbu, and Bhaka Tulku among many others. Finally, special thanks to my friends, artist comrades, collaborators, and collectors who have consistently encouraged me over the course of four decades: Terry Wunderlich, Catherine McCliment, Randy Canaday, Bill Renschler, Scott Presti, Andy Mahler, Ray Conner, Leslie Barany, Jacques Baruch and many others.

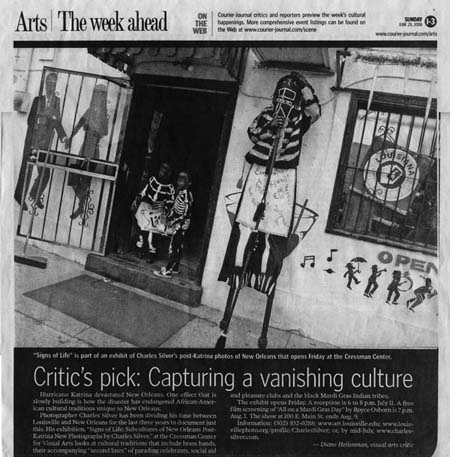

Review - Louisville Courier-Journal - 2008